Five young economists from Deloitte have rejected calls to lower immigration to alleviate housing pressures, instead arguing that migrants are part of the housing solution:

The young economists argue migration is a solution to the housing supply gap rather than a problem because it will help fill skills shortages in the construction industry.

They say Australia needs a 41% increase in its construction workforce to meet Labor’s target of building 1.2 million new homes by 2030, and that both apprentices and migrants could fill the gap.

Deloitte found that migrants make up 24.2% of construction workers, short of the economy-wide average of 32%. “Cutting migration is not a viable long-term solution”, the report said.

This clashes with the view of Australians aged over 35, who in a recent poll by the Macquarie University Housing and Urban Research Centre said immigration was the biggest factor in the housing affordability crisis.

Hilariously, the young economists’ report coincided with new research from the Housing Industry Association (HIA) that admitted that demand from strong immigration has overwhelmed housing supply, delivering a chronic shortage of homes that has driven up prices and rents:

“I remember when the (1.2 million homes) estimate first came out, we were running population assumptions that just to keep affordability from getting worse, we needed 200,000 homes a year,” HIA senior economist Tom Devitt.

“But that was before population growth really surprised everyone over the past few years, and it’s remained more elevated than what anyone, including government, thought”…

He said the current goal of 240,000 homes a year under the Housing Accord was now not even enough to stop housing affordability getting worse.

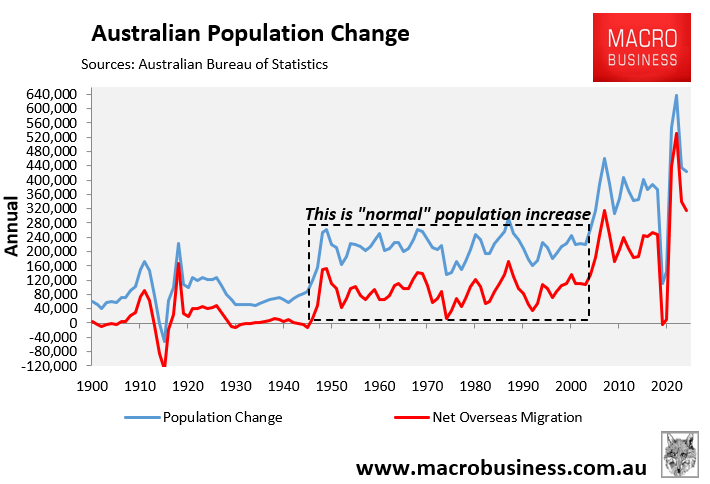

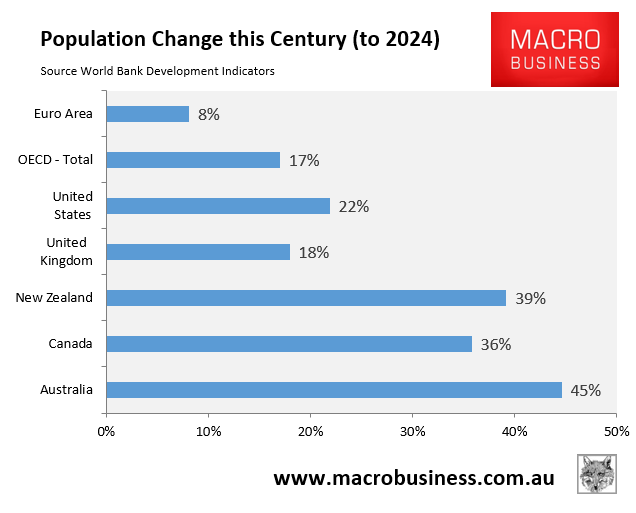

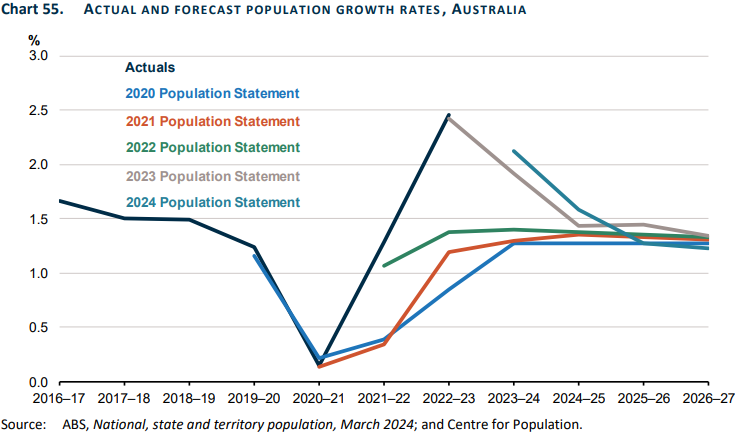

Let’s get real. Australia has experienced the strongest population growth this century in the advanced world, following 20 years of extreme immigration that began in the mid-2000s:

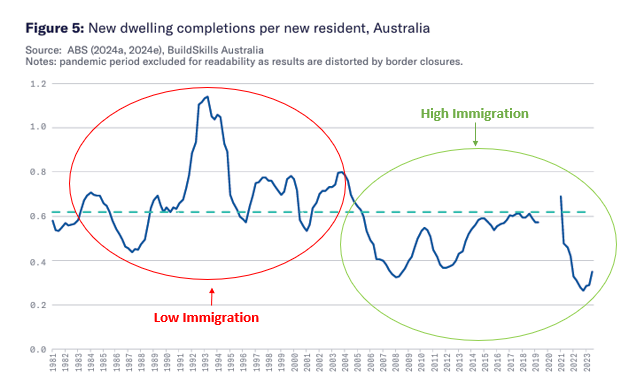

According to Build Skills Australia, the building rate per new resident plummeted, despite the fact that the number of homes built over the last 20 years (174,000 dwellings annually) has been significantly higher than the previous 20 years (145,400 dwellings annually):

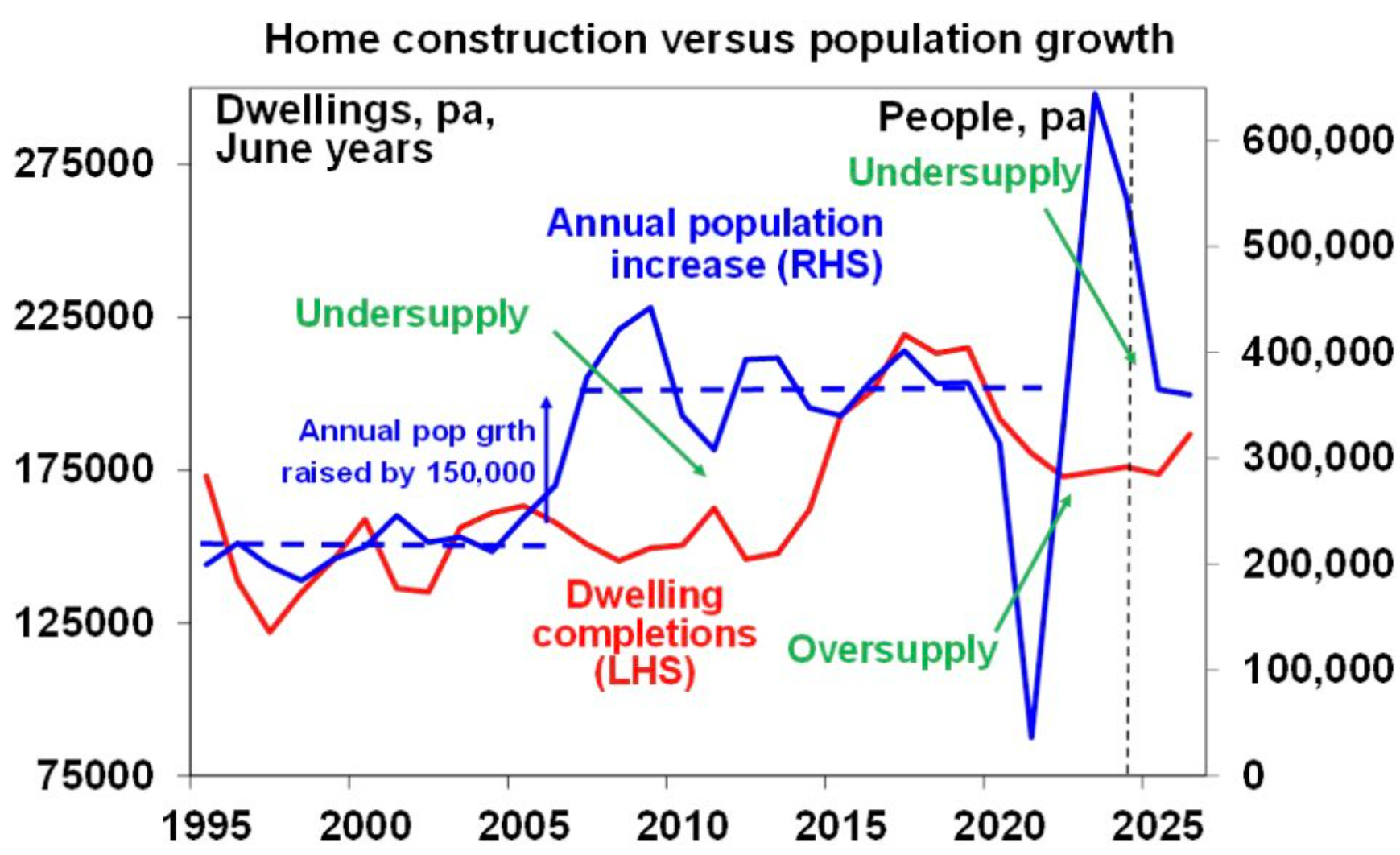

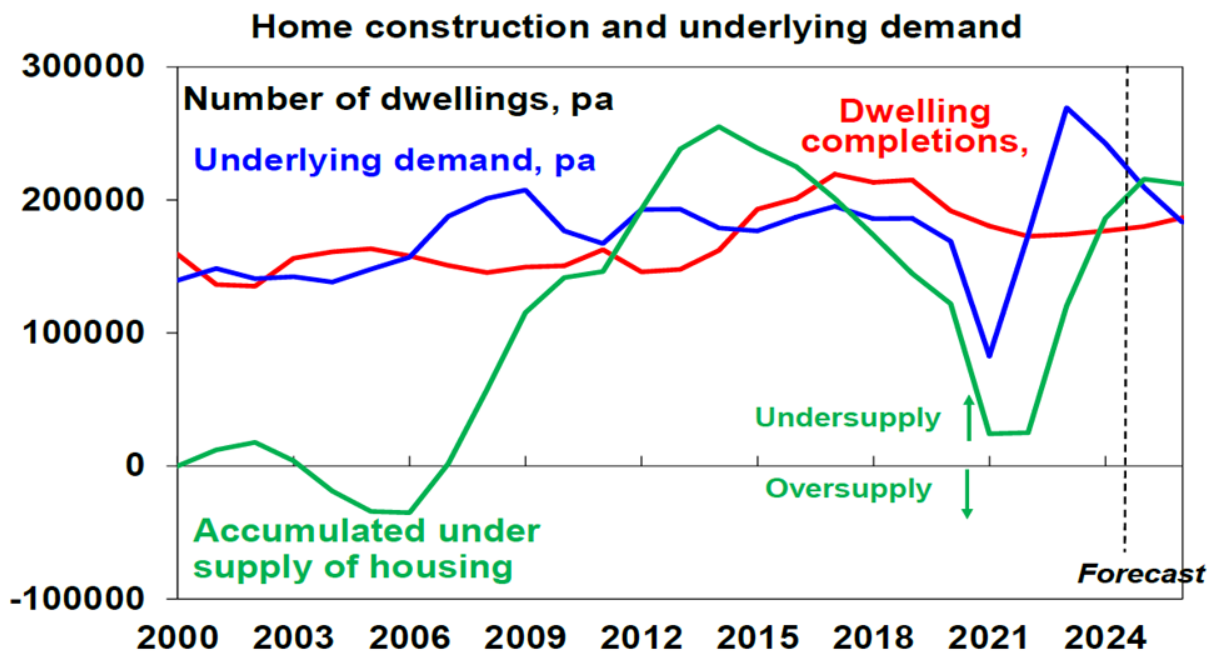

The following chart from AMP chief economist Shane Oliver illustrates that after immigration more than doubled and annual population growth jumped by 150,000, Australian housing became structurally undersupplied:

“Australian housing is chronically undersupplied”, Oliver wrote in July.

“This has been the case since the mid-2000s when immigration levels, and hence population growth, surged and the supply of new homes did not keep up. Our assessment is that the accumulated housing shortfall (the green line in the next chart) is around 200,000 dwellings at least and possibly 300,000 depending on what is assumed in terms of the number of people per household”.

“The economic reality is that when underlying population driven demand for housing exceeds its supply prices rise and that is what we have been seeing for the last twenty years. The capital gains tax discount, negative gearing and foreign demand may have played a role, but they have been a sideshow to this demand/supply imbalance”, Oliver wrote.

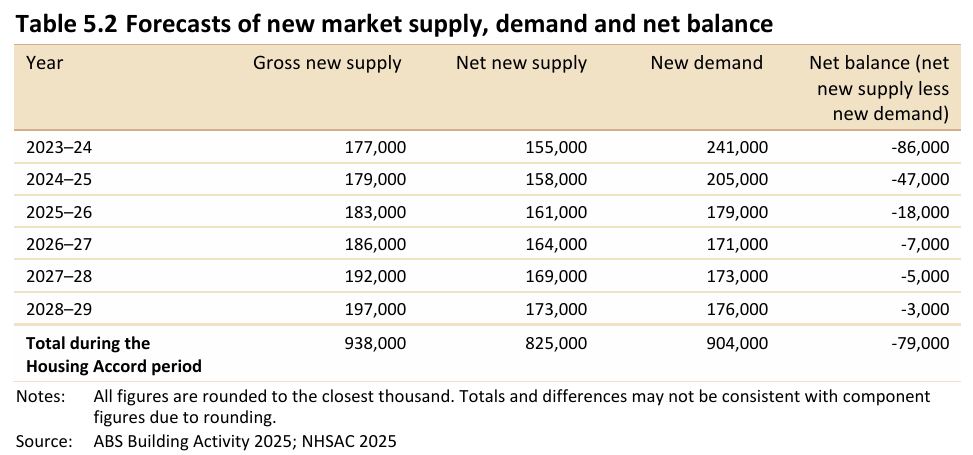

The National Housing Supply and Affordability Council’s (NHSAC) latest State of the Housing System report forecasts that new net housing supply will remain below population demand over the five years to 2028–29, resulting in an additional cumulative undersupply of 79,000 homes.

NHSAC warned that ongoing strong population growth relative to supply will push up rents and lead to more homelessness and overcrowding.

“The excess of new demand relative to new supply over the Housing Accord period will worsen the existing undersupply of housing in the system and add to affordability pressures”, NHSAC said.

“Rental housing will remain scarce for households across the income spectrum as the vacancy rate remains below its historic average”.

“A lowered vacancy rate will absorb some of the unmet demand, and some will add to the homeless population. Some may be absorbed by suboptimal types of shelter not captured by traditional measures of the housing stock, such as caravan parks, hotels and emergency shelters. Most will be absorbed by households not forming that otherwise would have, resulting in larger households and more instances of overcrowding”, NHSAC warned.

Given its reliance on the Centre for Population’s net overseas migration (NOM) forecasts, which are always conservative (see below), NHSAC’s estimated housing shortage is also likely to be conservative.

The Centre for Population projects a reduction in NOM to 255,000 per year in 2025-26 and then NOM of 225,000 per year for the remainder of the forecast period.

However, former senior immigration bureaucrat Abul Rizvi recently forecast that Australia’s NOM would average around 300,000 based on current immigration settings.

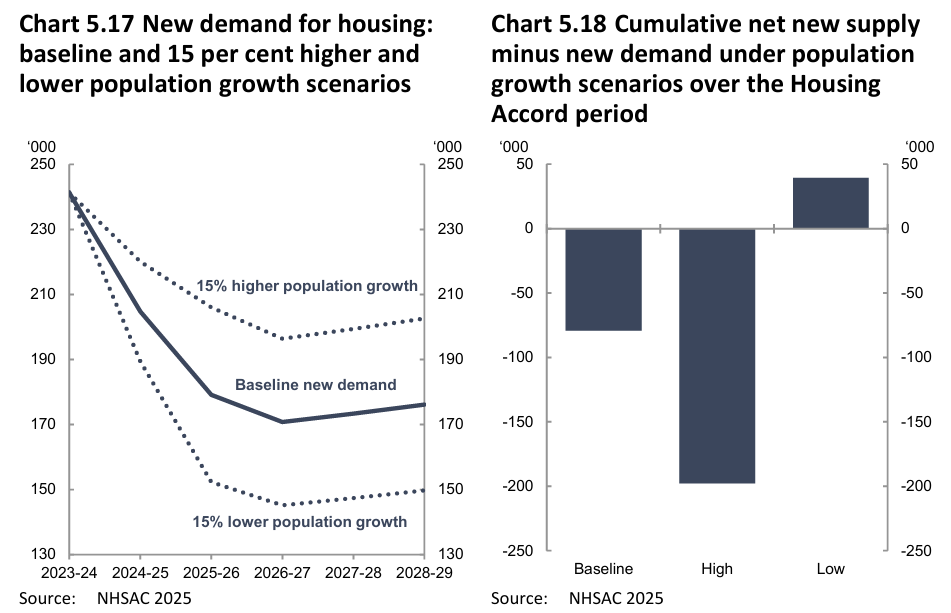

If Australia’s population grows 15% faster than projected, which seems more likely, NHSAC forecasts that the projected housing shortage will increase to around 200,000 over the five years to 2028-29, taking Australia’s cumulative housing shortage to around 400,000.

s

On the other hand, NSAC’s sensitivity analysis projected a surplus of 40,000 homes over five years if population growth is just 15% less than the Centre for Population’s baseline forecast.

The above sensitivity analysis from NHSAC proves that the primary solution to the nation’s housing shortage is to cut immigration to a level below the nation’s capacity to build housing and infrastructure.

This brings me to the second part of the young economists’ argument: that migrants are a solution to the housing crisis.

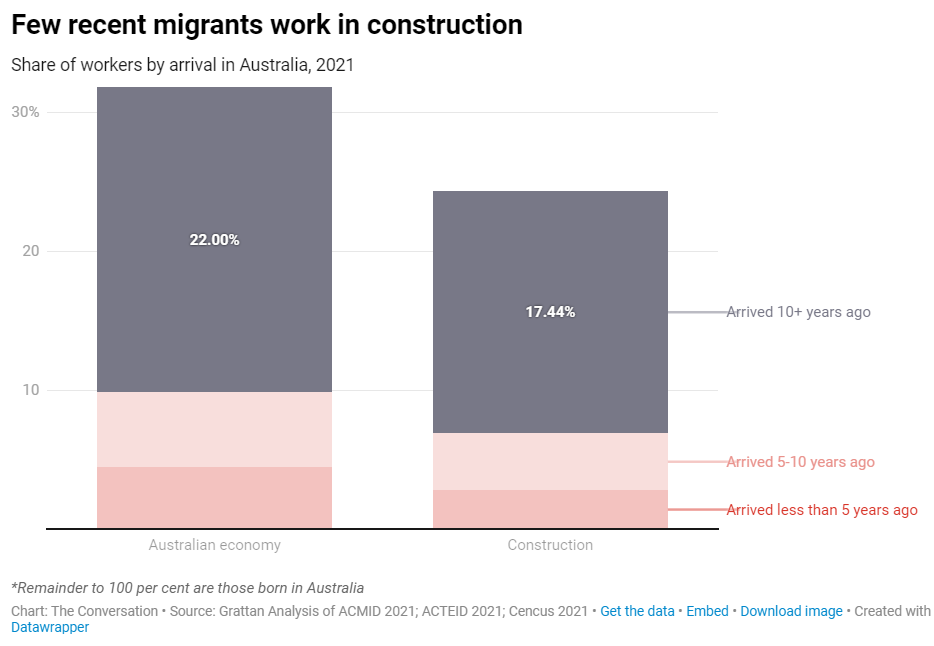

Build Skills Australia noted in its latest report that few recent migrants actually work in construction:

Over the last 20 years, the residential construction sector has consistently employed between 4.0% and 5.0% of the working-age population in Australia… If immigration is to make a net positive contribution to labour supply, the proportion of immigrants employed in residential construction must exceed this ‘hurdle rate’ of 4.0%-5.0%. Otherwise, local resources will need to be diverted from other activities to meet the housing needs of the growing population.

However, only 3.2% of recent immigrants—those who arrived in the last decade—are employed in the residential construction sector. This indicates that immigration’s contribution to population growth has not been matched by its contribution to the workforce needed to construct housing for these additional residents…

As it stands, the residential construction share of the immigration intake must increase by as much as 40% before it can be considered a viable strategy for boosting labour supply.

Build Skills Australia’s analysis aligns with data compiled by the Grattan Institute, showing that migrants are vastly underrepresented in the construction industry:

“Migrants who arrived in Australia less than five years ago account for just 2.8% of the construction workforce, but account for 4.4% of all workers in Australia”, Grattan reported.

Leading pro-Big Australia shills Peter McDonald and Alan Gamlen also admitted that Australia’s immigration is worsening Australia’s housing and infrastructure shortages by lifting demand without adding to labour supply:

“In 2023-2024, the permanent programme delivered just 166 tradespeople, negligible against national needs. By contrast, more than 5,000 entered via the temporary skilled stream in 2024-2025”.

“Even this is insufficient to close the gap”.

The bottom line is that Australia’s immigration system is directly driving Australia’s housing and infrastructure shortages by adding far more to demand than they do to supply.

The optimal solution, therefore, is to run a significantly smaller migration program that prioritises quality over quantity and fills genuine skills shortages.

Otherwise, Australia’s housing shortage and infrastructure shortages will worsen.

Why won’t Deloitte’s young economists acknowledge these basic facts? Are they really so woke that they ignore what is obvious?