The Australian Financial Review recently reported that the cost of the NDIS continues to escalate.

According to the latest data, the cost growth in NDIS plans was 9.5% year-on-year in the September quarter, with expense growth up by 10.1%.

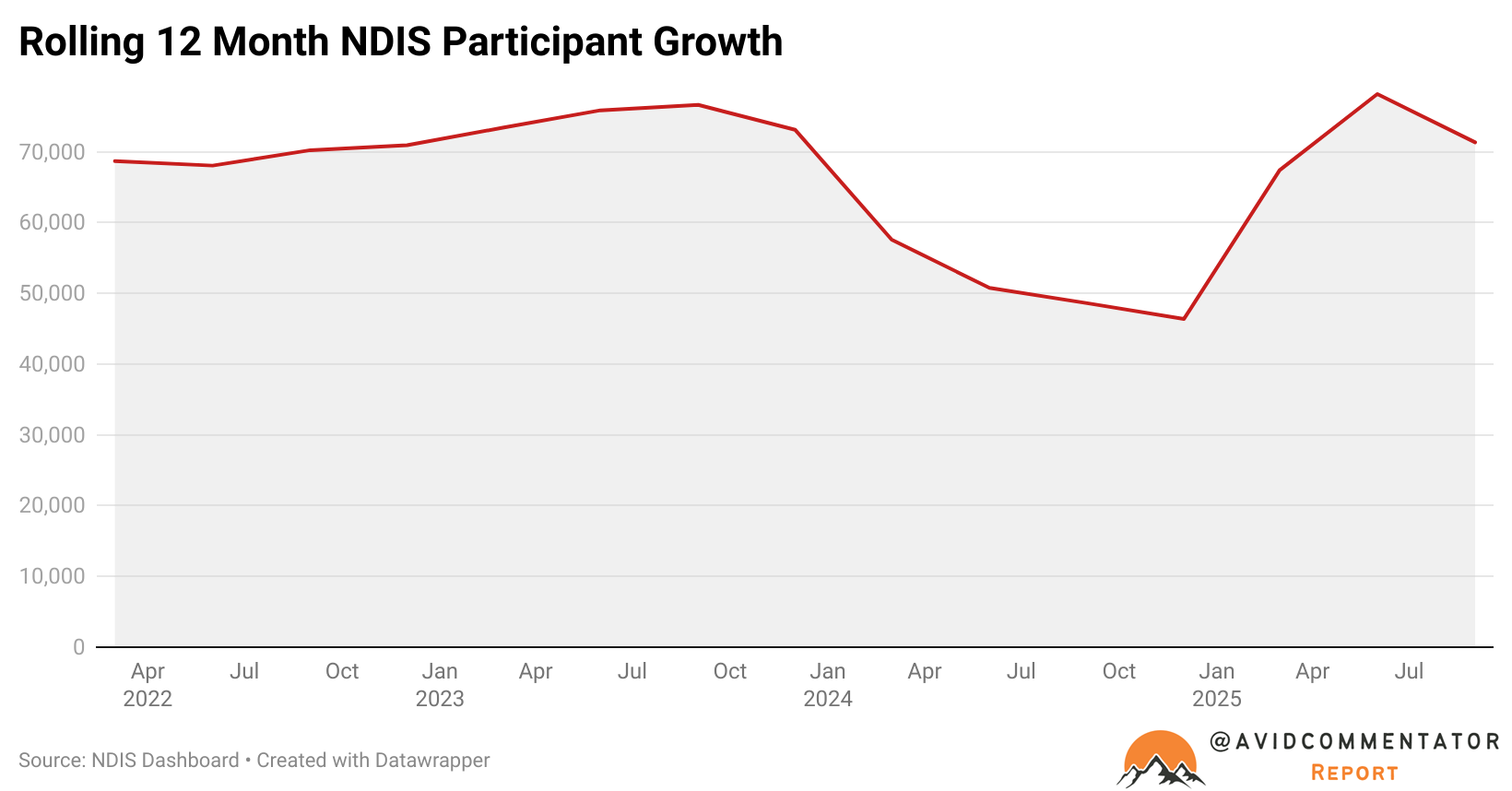

Examining these numbers clearly warranted a closer look at the system’s participant growth.

Since the end of the pandemic in the December quarter of 2021 and the September quarter of this year, the NDIS has added a little over 249,000 participants.

In the last 12 months of data, 71,300 participants have been added to the NDIS.

On a rolling 12-month basis, the NDIS has seen average growth in the number of participants of 66,500, with the highest-ever growth figure achieved in the June quarter, adding 78,100 participants.

At its most prevalent by age and gender, 16% of six-year-old boys are NDIS participants.

As of the latest data, there are 751,400 NDIS participants, with 170,800 being children under the age of 9.

There is currently a proposal from the Albanese government to shift children with mild autism off the NDIS and onto a separate program called ‘Thriving Kids’ in a move to cut costs and deliver better outcomes.

But with the proposal requiring the states to match the federal government’s $2 billion in funding commitments, whether it will come to pass is another matter.

While these additional costs are collectively placing significant pressure on the federal budget, they are also playing a role in supporting the economy.

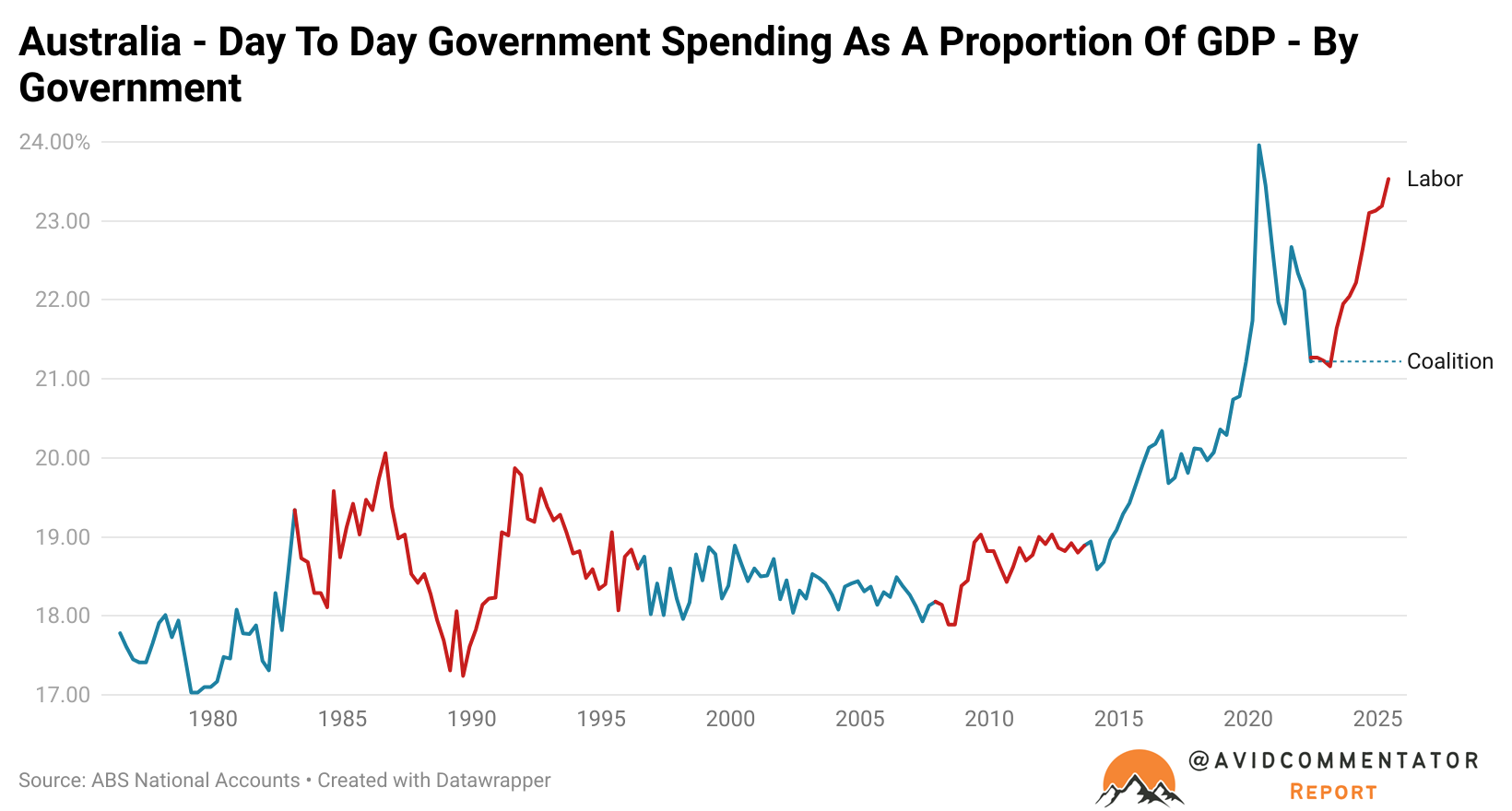

By growing the size of government as a proportion of GDP, the Albanese government, along with state and local governments, has been supporting the economy for most of the last three years.

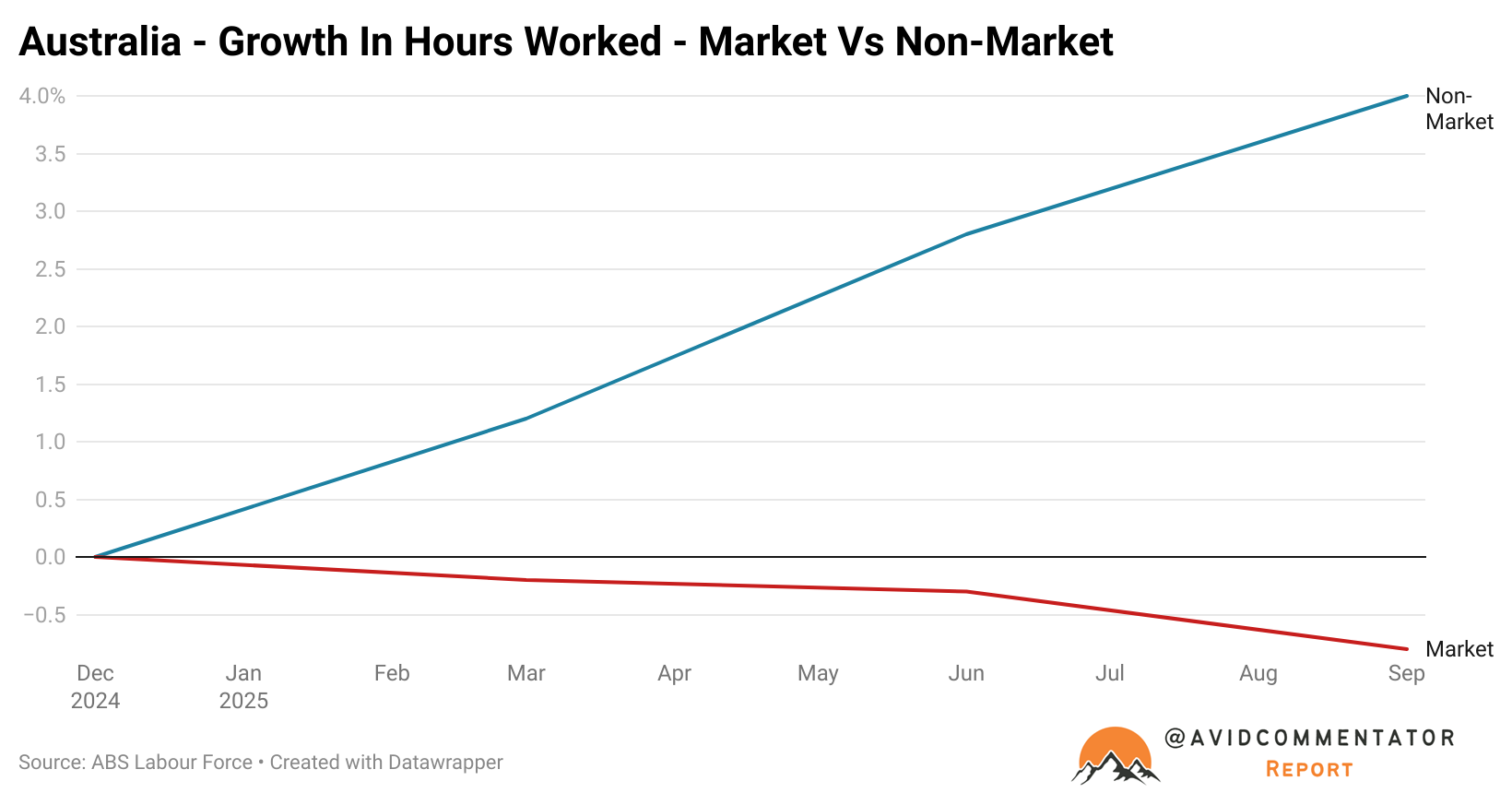

Meanwhile, the latest data from the ABS Labour Force Survey reveals that growth in hours worked for the non-market sector represents all net growth in hours worked during 2025.

While this is not the ideal source for assessing this metric, it is currently the most up-to-date data source until the labour account is released next month.

The Takeaway

While the NDIS and growth in government more broadly have played a pivotal role in supporting the economy, they are not sustainable strategies in the long term.

Looking at the relationship between the states and the Albanese government, fault lines are becoming increasingly clear.

Recently the Albanese government wrote to the states demanding they rein in spending on hospitals.

According to ABC News, the letter stated:

“For states and territories to realise a Commonwealth contribution of 42.5 per cent of public hospital costs by 2030-31, under the capped glide path model, it will be necessary for your government to work to reduce growth in hospital activity and costs to more sustainable levels,”

The demand resulted in a swift response from state health ministers.

“Upon reading the letter, my immediate response was that it was almost beyond belief that the prime minister would write to us saying we have to work to reduce growth in hospital activity,” Queensland Health Minister Tim Nicholls said

“Demand is growing with an older and growing population with more severe acuity and presentations, it’s just unrealistic to expect the states to say, ‘oh, well, we can control demand”, he stated

Ultimately, relying on the growth of government to support the economy is not sustainable in the long term, as evidenced by the challenges faced by the Starmer government in Britain.

But that doesn’t necessarily mean that government in Australia as a proportion of GDP will stop growing any time soon; there is arguably scope for that to continue at a federal level for quite some time.