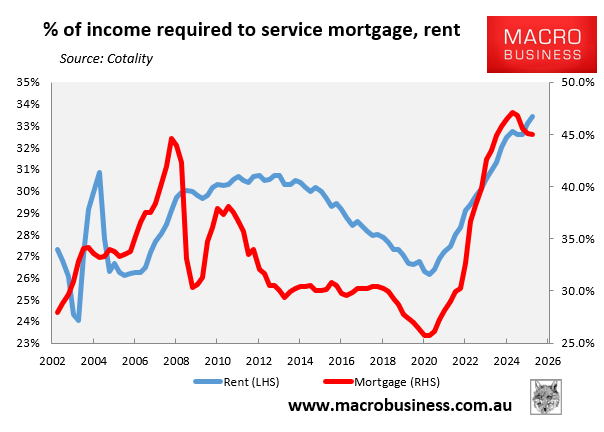

This week, Cotality released its housing affordability report for the September quarter of 2025, which reported abysmal affordability across the nation for both purchases and rent.

In response, AMP chief economist Shane Oliver produced a report explaining how Australia’s mass immigration policy has eroded housing affordability by creating a structural imbalance between supply and demand.

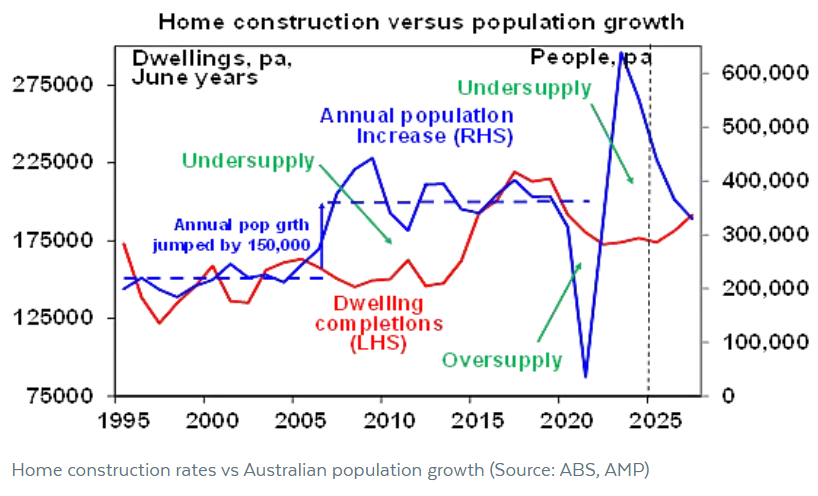

Oliver explains how the nation’s housing market became structurally undersupplied when the federal government ramped up immigration in the mid-2000s, expanding Australia’s population growth by 150,000 annually.

This shortage was gradually eroded by the high-rise apartment construction boom between 2015 and 2019, as well as the collapse in immigration during the Covid-19 pandemic.

However, following the record immigration influx post-pandemic, the shortage has worsened again.

According to Oliver:

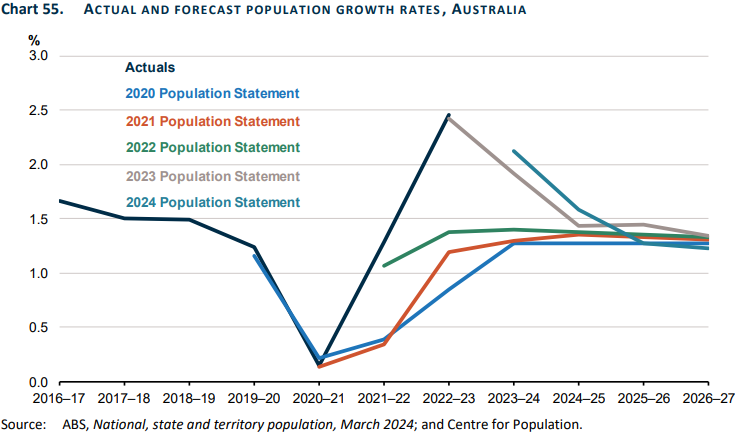

Starting in the mid-2000s annual population growth jumped by around 150,000 people largely due to a surge in net immigration – see the blue line in the prior chart.

This should have been matched by an increase in dwelling completions of around 60,000 homes per annum but there was no such rise until the unit building boom of 2015-20 leading to a chronic undersupply of homes – see the red line.

The unit building boom and the slump in population growth through the pandemic helped relieve the imbalance but the unit building boom was brief and a decline in household size from 2021 resulted in demand for an extra 120,000 dwellings on the RBA’s estimates. The rebound in population growth post the pandemic then took property market back into undersupply again.

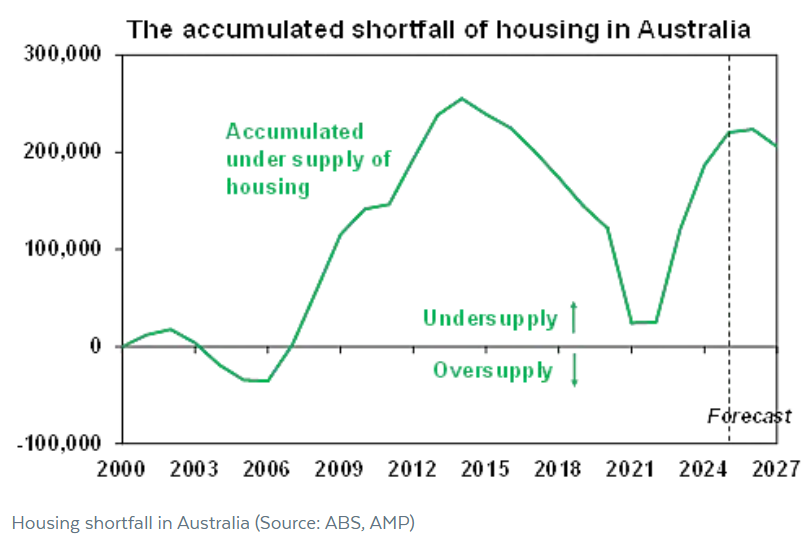

Shane Oliver conservatively estimates that Australia’s cumulative housing shortage is currently sitting at around 220,000, but it could be as high as 300,000:

Up until 2005 the housing market was in rough balance. It then went into a massive shortfall of about 250,000 dwellings by 2014 as underlying demand surged with booming immigration. This shortfall was then cut into by the 2015-20 unit building boom and the pandemic induced hit to immigration.

But it’s since rebounded again to around 220,000 dwellings, or possibly as high as 300,000 if the pandemic-induced fall in household size is allowed for. The shortfall is confirmed by low rental vacancy rates.

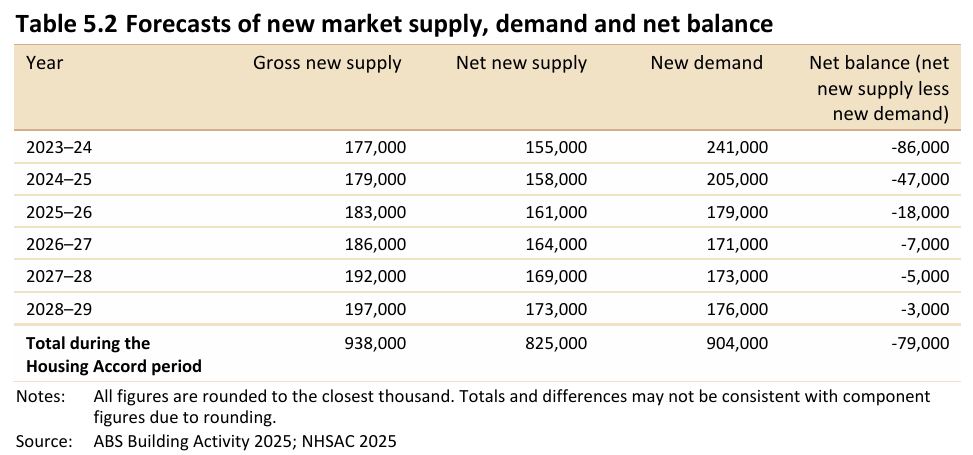

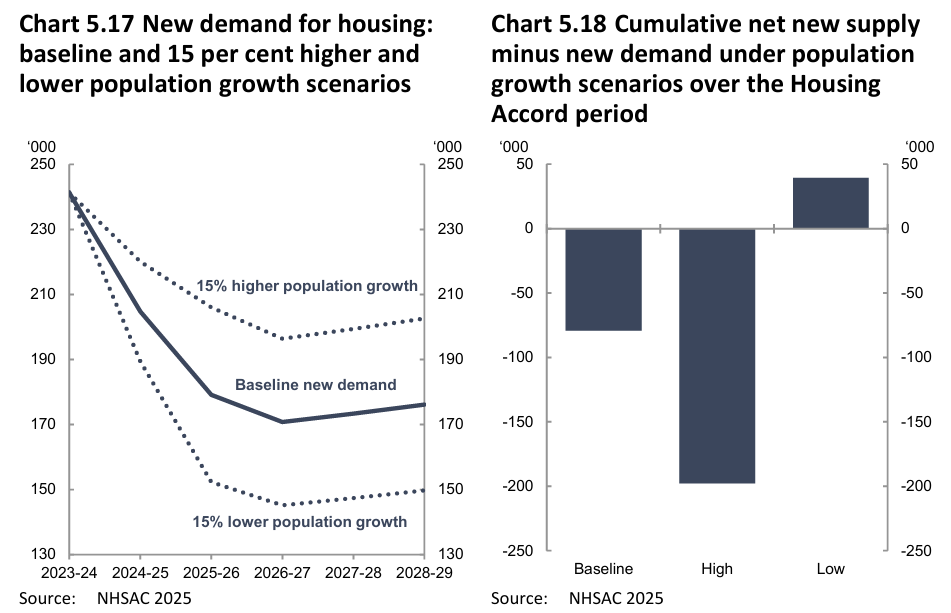

At this point, it is worth adding the latest forecasts from the National Housing Supply and Affordability Council (NHSAC), which project that new net housing supply will remain below population demand over the five years to 2028–29, resulting in an additional cumulative undersupply of 79,000 homes.

NHSAC also warned that ongoing strong population growth relative to supply will push up rents and lead to more homelessness and overcrowding.

NHSAC’s baseline 79,000 shortage is based on the Centre for Population’s net overseas migration (NOM) forecasts, which tend to be conservative (see below).

The Centre for Population projects a reduction in NOM to 255,000 per year in 2025-26 and then NOM of 225,000 per year for the remainder of the forecast period.

However, former senior immigration bureaucrat Abul Rizvi recently forecast that Australia’s NOM would average around 300,000 based on current immigration settings.

If Australia’s population grows 15% faster than projected, which seems more likely, NHSAC forecasts that the projected housing shortage will increase to around 200,000 over the five years to 2028-29, taking Australia’s cumulative housing shortage to around 400,000.

s

On the other hand, NSAC’s sensitivity analysis projected a surplus of 40,000 homes over five years if population growth is just 15% less than the Centre for Population’s baseline forecast.

Shane Oliver recommends that NOM be reduced to 200,000 to ease the housing shortage:

First, match the level of immigration to the ability of the property market to supply housing and reduce the accumulated housing shortfall of around 200,000-300,000 dwellings. – we have clearly failed to do this since the mid-2000s and particularly following the reopening from the pandemic, and this is evident in the ongoing supply shortfalls. Our rough estimate is that immigration needs to be cut back to around 200,000 a year from 316,000 over the year to the March quarter.

In my view, 200,000 NOM is still far too high. It is only 10% below the pre-pandemic average level that caused the shortage in the first place, which was only alleviated by the 2015-19 high-rise shoebox apartment boom (many of which were poor quality and defective).

Australia should not repeat the same mistakes again. NOM should be cut below 150,000 and focused on genuinely highly skilled migrants that the nation actually needs (e.g., more tradies, less Uber drivers).

These minor gripes aside, I welcome Shane Oliver’s contribution to the housing-immigration debate, especially his hard numbers around supply and demand.